In the past 100 years, the use of wood has generally been limited to light timber framing, generally no more than three to six stories high — structurally, the practical limit for that type of construction. But in the past 10 to 15 years, the development of new heavy timber products — cross laminated timber (CLT), glued laminated wood (glulam), and laminated veneer lumber (LVL) — has opened the door to taller and bigger buildings with wood as the primary building material.

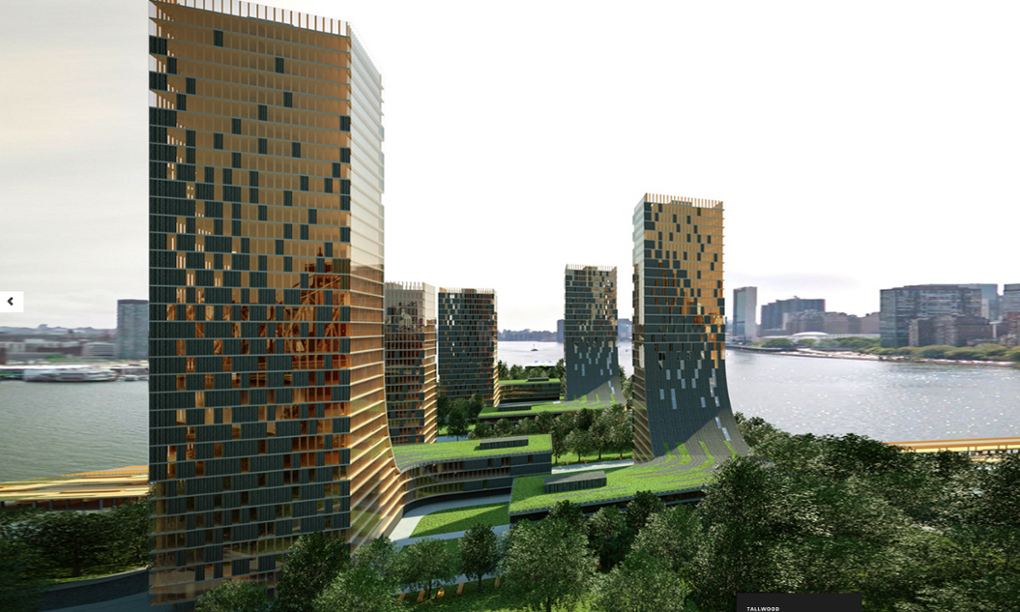

For Vancouver-based architect Michael Green, the sky is the limit for wooden buildings. While nearing completion of the University of Northern British Columbia’s Wood Innovation and Design Centre in Prince George, Green’s practice, MGA, has also drawn up plans for a 30-storey, sun-grown tower for downtown Vancouver.

If built, Green’s vision would be easily the world’s tallest wooden building, soaring past the current contenders – London’s Stadthaus at nine storeys, and the 10-storey Forte Building in Melbourne. But that’s not the main motivation, according to MGA associate Carla Smith. “To be honest, it’s not like we really care about being the tallest,” she says. “We really do see a wooden future for cities, and our aim is to get others to jump on board too.”

Green is giving away his hefty, 200-page instruction manual, The Case for Tall Wood Buildings, free of charge. He hopes it will inspire architects and engineers to branch out beyond their concrete and steel confinements, and embrace a material that sequesters carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, holding it captive during its growth and lifetime in a structure – one tonne of CO2 per cubic metre of wood. To put that in context, while a 20-storey wooden building sequesters about 3,100 tonnes of carbon, the equivalent-sized concrete building pumps out 1,200 tonnes. That net difference of 4,300 tonnes is the equivalent of removing 900 cars from the city for a year.

The most promising realisation of wood’s worth is in New Zealand, where the violent earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 left almost one third of the Christchurch’s buildings – including 220 heritage sites – up for demolition. Almost four years on, the city’s grand rebuild has begun, and wood has taken a step into the spotlight due to its durability in high-seismic activity zones. The “new” Christchurch, as outlined in the Central Recovery Plan, is proposed to be a low-rise, “greener, more attractive” city costing around NZ$40bn, almost 20% of the country’s annual GDP.

See Michael Green's TED talk over here

No comments:

Post a Comment